The morning of June 11, a Klaxon alert told me that Tommy Langaker’s name had just dropped off the list of competitors at ADCC, the world’s most prestigious submission grappling tournament.

In this weird, niche sport that I obsess over, this was an early warning sign, a rumble before an avalanche. Athletes who’d spent years trying to reach ADCC were jumping to a rival tournament, the Craig Jones Invitational.

Submission grappling, as a professional sport, is younger than most of its competitors, and some of them are teenagers. There is no unified ruleset or governing body. Full-time athletes regularly enter tournaments alongside part-time hobbyists.

For fans of the sport, the peak of the competition calendar is the Abu Dhabi Combat Club championship, or ADCC, a tournament founded by Sheik Tahnoon Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the son of UAE’s first president and now its national security advisor and brother of the current president.

Held every other year, ADCC is often called “the Olympics of submission grappling,” though few outside the sport even know it exists. It is like the Olympics in one way: the winners earn more in fanfare and prestige than cash, even as participating athletes have become ever more professionalized.

The sport itself can look like wrestling, except you win by making your opponent submit using a joint lock or stranglehold. Since a pin doesn’t end the fight, it’s normal for grapplers to fight from the bottom, working to off balance the top player or entangle limbs. Levi Jones-Leary, who ultimately finished second at CJI, started every match by sitting down in front of his opponent.

No grappler is making a living off prize money, because most tournaments offer little to no prize money. Those who treat it like a job hustle for sponsorships and teach seminars and sell instructional videos.

One of those athletes, two-time ADCC silver medalist Craig Jones, raised several million dollars from unnamed funders to challenge ADCC’s dominance. He scheduled a rival tournament – the Craig Jones Invitational – for the same weekend as this year’s tournament, offering a million-dollar prize to the winner.

With the two organizers fighting over the same competitors, I set up a Klaxon alert on each tournament’s roster.

And in June, it happened. “Has Tommy Langaker said anything about CJI?” I posted in a Discord group for grappling fans. “His name just dropped off the ADCC list.” I found Langaker’s sudden absence surprising, since he had won ADCC’s European trials, a grueling competition in itself, to qualify for this year’s championship.

It took three more days for Langaker to formally announce he was dropping out of ADCC to compete at CJI, Jones’ competing event. Other athletes followed, and Klaxon emailed me each time, as the two tournaments jostled for the best athletes in the sport.

I spent most of the summer obsessing over the fight between these two tournaments and their organizers, and in doing so, I leaned on some of MuckRock’s core tools: FOIA requests, DocumentCloud and Klaxon.

What does it cost to run the biggest submission grappling events in the world?

Jones and Jassim spent the spring and summer sniping at each other over social media, but at the heart of the dispute was money: What does it cost to run the biggest submission grappling events in the world?

ADCC’s main organizer, Mo Jassim, spent lavishly on 2022’s world championship to turn the tournament into a premier spectacle. The UFC’s Bruce Buffer announced fights and taiko drummers played between bouts. When Jassim changed the venue to T-Mobile Arena in 2024, it raised the cost even more.

Many athletes who were competing at ADCC asked why money was going to a venue and not to them, given the brewing controversy around underpaid fighters. Several competitors, including 2022 champion Ffion Davies, said they could make more money in other events, and that doing a tournament just for exposure and prestige wasn’t worth it.

Jassim’s original venue, the Thomas & Mack Center, is part of the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, and therefore subject to Nevada’s public records laws. And because Jones thought it would be a good troll to hold his event at the same venue as the last ADCC, we can see what both promotions spent in the same place.

I filed three public records requests with the University of Nevada-Las Vegas:

-

May 29: the booking contract for CJI

-

June 20: contracts and ticket sales for ADCC 2022

-

Sept. 9: final sales and contract amendments for CJI

To be honest, I didn’t think UNLV would give me any of this. Events are a big business and I expected the university to find an excuse or an exemption to keep sales figures private. To its credit, UNLV fulfilled each of these requests in about a week, with no redactions.

Did CJI earn enough in ticket sales to cover its huge prizes?

Besides poaching competitors, CJI made waves for its massive prize pool:

-

$1 million to each of the two divisions’ winners (Nick Rodriguez and Kade Ruotolo)

-

$20,000 for best submission (Lucas Kanard)

-

$50,000 for most exciting grappler (Andrew Tackett)

-

$10,001 show money for 16 competitors

-

Unknown show/prize money for the superfight between Ffion Davies and Mackenzie Dern

-

Unknown show money for Gabi Garcia

Jones told podcaster Joe Rogan that a mystery funder was covering costs entirely, and ticket sales would go to charity. The CJI organizers have not released sponsorship figures or ad revenue, which was streamed live on YouTube for free.

So, did its ticket sales equal its prizes? No. But it did net slightly more than ADCC did in 2022.

CJI sold a total of 6,823 tickets. That earned about $864,512 in gross revenue. The Thomas & Mack Center kept $254,952 to cover costs, including what CJI had prepaid, eventually paying out $674,560 to Jones’ organization, the Fair Fight Foundation.

In 2022, its most recent event, ADCC sold 10,238 tickets, earning $1,099,980 in gross revenue.

Across almost all venue categories, ADCC spent more than CJI, despite paying less in rent. It spent $352,823 on services provided by Thomas & Mack, almost $100,000 more than CJI.

| Cost comparison | ADCC 2022 | CJI 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Rent, including load-in | $80,000 | $90,000 |

| Front-of-house | $175,248.20 | $79,622.04 |

| Back-of-house | $44,948.50 | $39,784.50 |

| Total venue charges | $352,822.50 | $254,951.60 |

| Net revenue | $666,333.46 | $674,560.35 |

ADCC’s total prize pool in 2022 was $230,600, according to its website. The highest payouts went to the winners of the open weight division and superfight – Yuri Simões and Gordon Ryan, respectively. Men’s division winners earned $10,000; women earned $6,000.

Two months after ADCC, Jassim resigned as head organizer for the tournament. Jones has promised to host CJI again. On Dec. 7, he announced on Instagram that he’d secured funding for a tournament in August 2025.

One person who likely out-earned every athlete at ADCC 2022 only briefly set foot on the mats: Bruce Buffer charges from $40,000 to $74,999 for his role as a ring announcer.

Read every document used in this story

The tweets started trickling out in late November. One might fairly describe them as disgruntled.

Bellator bantamweight champion Patchy Mix called it “frustrating” to have two straight fights canceled. Light heavyweight champion Corey Anderson wrote that he was “aging like warm cheese” waiting for his next fight to be booked. Featherweight champion Patricio Pitbull said he’d waited most of the year for a fight, then spent money on a training camp when he was finally given a date and an opponent, only to end up having the fight called off a month prior.

“We have no clue about when we might be fighting after two fight cancellations in a row,” Bellator bantamweight contender Leandro Higo wrote on X. “Time is of the essence in this game, we can’t waste our primes on the sidelines. I’m working hard to take that title, spending money, sweat and blood. What’s going on?”

This is the question many fighters on the Bellator roster are asking lately — and no answers seem to be forthcoming. After PFL bought Bellator from Paramount Global in November of 2023, company executives outlined plans to keep Bellator going as a separate, “reimagined” entity in 2024.

But as the year draws to a close, many Bellator fighters have taken to social media to complain of being shelved with little to no information on the company’s future plans for them. They remain under contract, unable to sign with another promotion like the UFC, but say they aren’t being offered fights.

Duke Roufus, the longtime coach of former Bellator bantamweight champion Sergio Pettis, was one of the first to take his complaints public.

“Sergio was supposed to fight on the [Nov. 29] card in Saudi Arabia, and the fight was pulled off the card,” Roufus said. “Word around the campfire was that it was because of finances, and that’s never a good thing to hear in this business. People say they’re waiting for an influx of money to come in, but a lot of these guys are at critical points in their careers. They don’t have time to waste on the bureaucracy of organization wars.”

Publicly, PFL executives have stayed mostly quiet on the subject. PFL officials did not reply to repeated requests for comment for this story. On X, where PFL chairman Donn Davis is an active poster, replies to virtually every tweet he sends are littered with fans asking about the status of Bellator fighters or demanding they be released from their contracts. Still, there’s been no public reply from anyone at PFL to lend clarity to the situation.

Some fighters say they were granted permission to fight in Japan’s Rizin organization while still under contract with Bellator. That was the case for bantamweight Juan Archuleta, who won the Rizin bantamweight title before later losing it to Kai Asakura last December. He was then released from his Bellator contract, Archuleta said, which allowed him to continue in Rizin. Some other fighters were given similar opportunities, he noted, but that came with a pay cut from what they’d been making in Bellator prior to the PFL sale.

“Before the sale, Mike Kogan and Scott Coker had bumped all our purses up,” Archuleta said. “They re-signed us and gave us a s*** ton of money for our contracts. Like, a s*** ton. And we were all like, this would be nice if they still honor it, but I already knew going into that change of [ownership] that [PFL wasn't] going to want to honor those contracts. It’s a lot of money for some guys.”

This appears to be at the heart of former Bellator champion Gegard Mousasi’s lawsuit against the company filed in October. Mousasi alleges that after signing an eight-fight contract extension with built-in escalators set to take effect in the second half of the deal, Bellator essentially stopped offering him fights.

Mousasi was released from his contract in May after voicing his discontent publicly in several interviews on the subject. Now he is seeking damages of at least $15 million, alleging not only breach of contract but also accusing Bellator and PFL of misclassifying him as an independent contractor.

MMA history has seen several instances of one promotion buying another, only to then experience some sticker shock at the price of some of the existing contracts. But as Roufus pointed out, despite the many complaints about fighter pay in the UFC, there were no such complaints about a refusal to honor contracts after the UFC purchased rivals like PRIDE FC and Strikeforce.

“You see this all the time with companies that come out and say they’re going to be the alternative to the UFC and they’re going to treat the fighters better,” Roufus said. “But I’ll say this: Next year will be my 20th year coaching fighters in the UFC. I’ve worked with elite guys to entry-level guys, and I’ve never seen the UFC renege on a contract or not pay a guy what he was owed or just shelve a guy like this. They always do what they say they’re going to do, and they usually do extra.”

Speaking to reporters after UFC 310 earlier this month, UFC CEO Dana White expressed sympathy with those fighters voicing their frustrations about the lack of bout offers.

“The last couple months we’ve been talking a lot about the PFL,” White said. “They’re canceling a lot of shows. I know a lot of guys that are supposed to fight, aren’t fighting. You guys know what the f*** is going on. When you see that start to happen, you’re running out of money. Things aren’t looking good, and you’re going to have people that want to jump ship.”

For now, those who might like to jump are instead being held in limbo. The wait for fights — and answers — goes on.

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (AP) — In the remotest reaches of Alaska, there’s no relying on DoorDash to have Thanksgiving dinner — or any dinner — delivered. But some residents living well off the grid nevertheless have turkeys this holiday, thanks to the Alaska Turkey Bomb.

For the third straight year, a resident named Esther Keim has been flying low and slow in a small plane over rural parts of south-central Alaska, dropping frozen turkeys to those who can’t simply run out to the grocery store.

Alaska is mostly wilderness, with only about 20% of it accessible by road. In winter, many who live in remote areas rely on small planes or snowmobiles to travel any distance, and frozen rivers can act as makeshift roads.

When Keim was growing up on an Alaska homestead, a family friend would airdrop turkeys to her family and others nearby for the holidays. Other times, the pilot would deliver newspapers, sometimes with a pack of gum inside for Keim.

Her family moved to more urban Alaska nearly 25 years ago but still has the homestead. Using a small plane she had rebuilt with her father, Keim launched her turkey delivery mission a few years back after learning of a family living off the land nearby who had little for Thanksgiving dinner.

“They were telling me that a squirrel for dinner did not split very far between three people,” Keim recalled. “At that moment, I thought ... ‘I’m going to airdrop them a turkey.’”

She decided not to stop there. Her effort has grown by word of mouth and by social media posts. This year, she’s delivering 32 frozen turkeys to people living year-round in cabins where there are no roads.

All but two had been delivered by Tuesday, with delivery plans for the last two birds thwarted by Alaska’s unpredictable weather.

Among the beneficiaries are Dave and Christina Luce, who live on the Yentna River about 45 miles (72 kilometers) northwest of Anchorage. They have stunning mountain views in every direction, including North America’s tallest mountain, Denali, directly to the north. But in the winter it’s a 90-minute snowmobile ride to the nearest town, which they do about once a month.

“I’m 80 years old now, so we make fewer and fewer trips,” Dave Luce said. “The adventure has sort of gone out of it.”

They’ve known Keim since she was little. The 12-pound (5.44-kilogram) turkey she delivered will provide more than enough for them and a few neighbors.

“It makes a great Thanksgiving,” Dave Luce said. “She’s been a real sweetheart, and she’s been a real good friend.”

Keim makes 30 to 40 turkey deliveries yearly, flying as far as 100 miles (161 kilometers) from her base north of Anchorage toward Denali’s foothills.

Sometimes she enlists the help of a “turkey dropper” to ride along and toss the birds out. Other times, she’s the one dropping turkeys while her friend Heidi Hastings pilots her own plane.

Keim buys about 20 turkeys at a time, with the help of donations, usually by people reaching out to her through Facebook. She wraps them in plastic garbage bags and lets them sit in the bed of her pickup until she can arrange a flight.

“Luckily it’s cold in Alaska, so I don’t have to worry about freezers,” she said.

She contacts families on social media to let them know of impending deliveries, and then they buzz the house so the homeowners will come outside.

“We won’t drop the turkey until we see them come out of the house or the cabin, because if they don’t see it fall, they’re not going to know where to look,” she said.

It can be especially difficult to find the turkey if there’s deep snow. A turkey was once missing for five days before it was found, but the only casualty so far has been a lost ham, Keim said.

Keim prefers to drop the turkey on a frozen lake if possible so it’s easy to locate.

“As far as precision and hitting our target, I am definitely not the best aim,” she joked. “I’ve gotten better, but I have never hit a house, a building, person or dog.”

Her reward is the great responses she gets from families, some who record her dropping the turkeys and send her videos and texts of appreciation.

“They just think it’s so awesome that we throw these things out of the plane,” Keim said.

Ultimately, she hopes to set up a nonprofit organization to solicit more donations and reach people across a bigger swath of the state. And it doesn’t have to stop at turkeys.

“There’s so many kids out in the villages,” she said. “It would be cool to maybe add a stuffed animal or something they can hold.”

___

Bohrer reported from Juneau, Alaska.

In May, we published a story diving into the nuances of the USDA plant hardiness zone map, which was updated in 2023 for the first time in a decade. I am a gardener AND a map nerd, so this was the juiciest, data-rich gardening story I was ever going to see. So we built an immersive story explaining what changed across the country, and what it means for our readers’ gardens.

It honestly feels like a Stefon meme. This app has EVERYTHING:

- Walking azaleas

- Rainbow D3.js charts

- “Mad Libs”-style, dynamic text for 30k+ places

- Naked figs in a freezer

- A color ramp with 26 unique colors

And of particular interest to this blog post:

- Self-hosted slippy maps

Slippy maps, which I’m defining here as pan-and-zoomable vector tile maps, can be quite costly to host with a third party like Mapbox. Historically, self-hosting was possible, but required a lot of technical expertise. But over the past two years, Kevin Schaul (Washington Post), Chris Amico (MuckRock) and others have outlined new approaches that lower the technical bar to self-hosting maps — and cost significantly less.

Here’s what we learned:

Skip building your own OSM layer. Use Protomaps’ daily download instead.

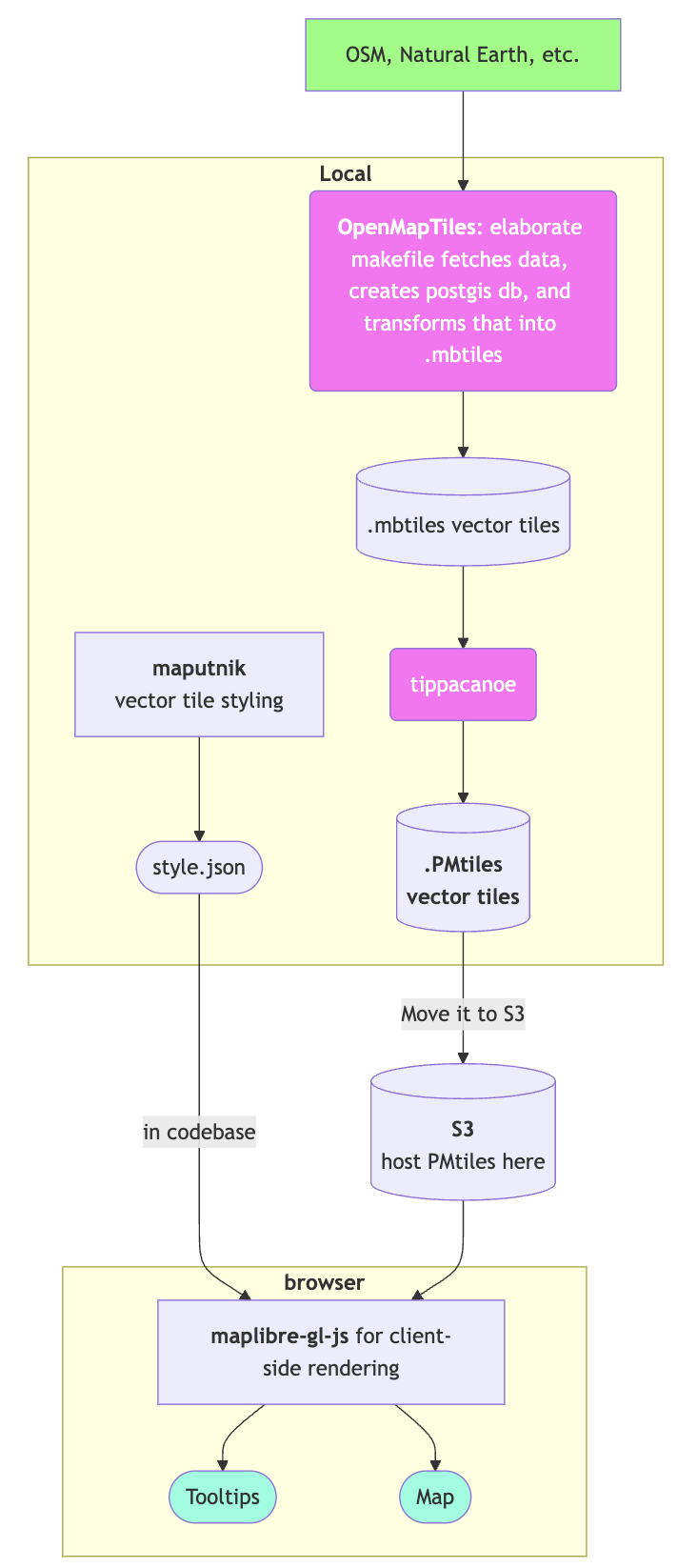

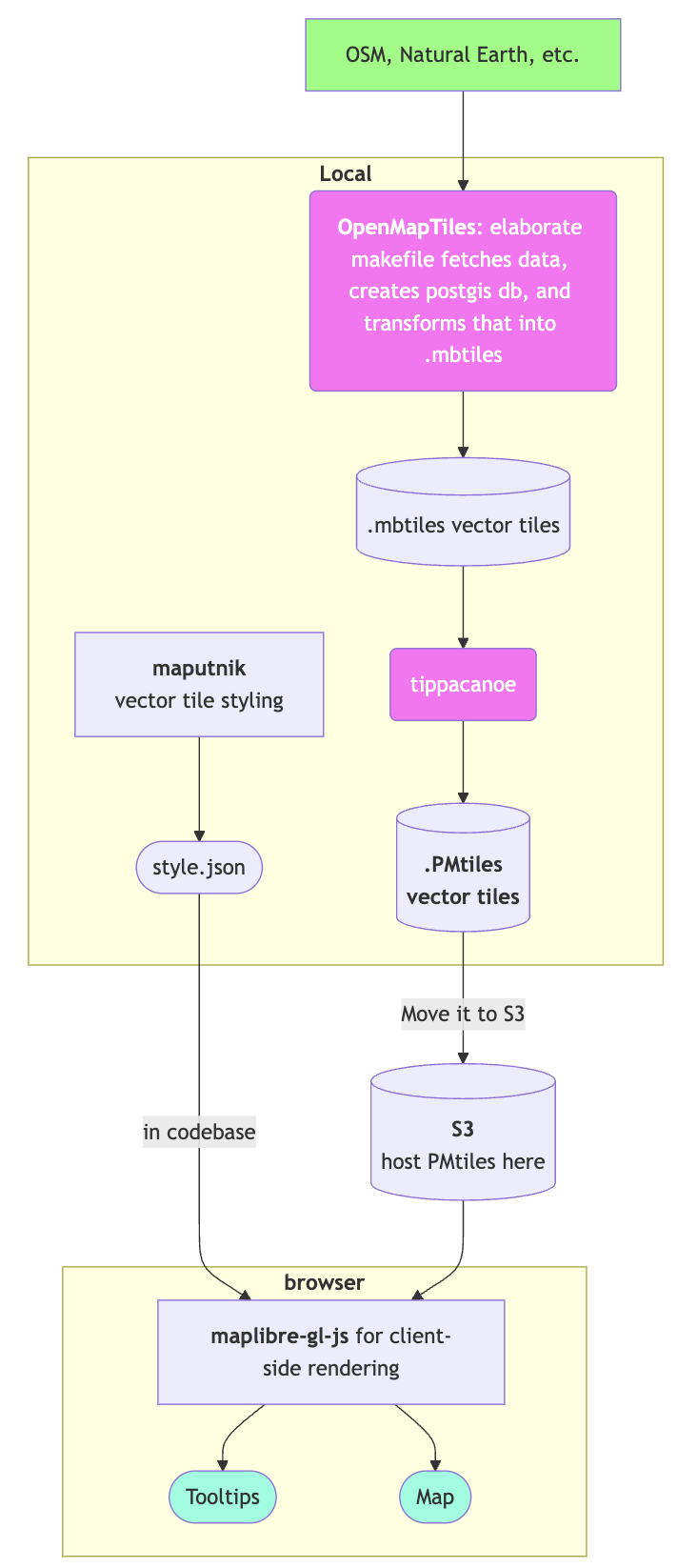

The tools that Schaul outlined fit together something like this:

Workflow with OpenMapTiles

It starts by baking your own OpenStreetMap and Natural Earth-based vector tiles via OpenMapTiles’ command line interface. I dove into it, but got totally overwhelmed. Confession time: I have never used Docker before, and I avoid PostGIS like the plague. I only recently learned what a makefile is. And that’s like…the whole thing.

[If you do want to go this route, I suggest following this workshop (videos 1, 2, 3, 4) to understand the ecosystem. They also have an easier-to-use paid tier.]

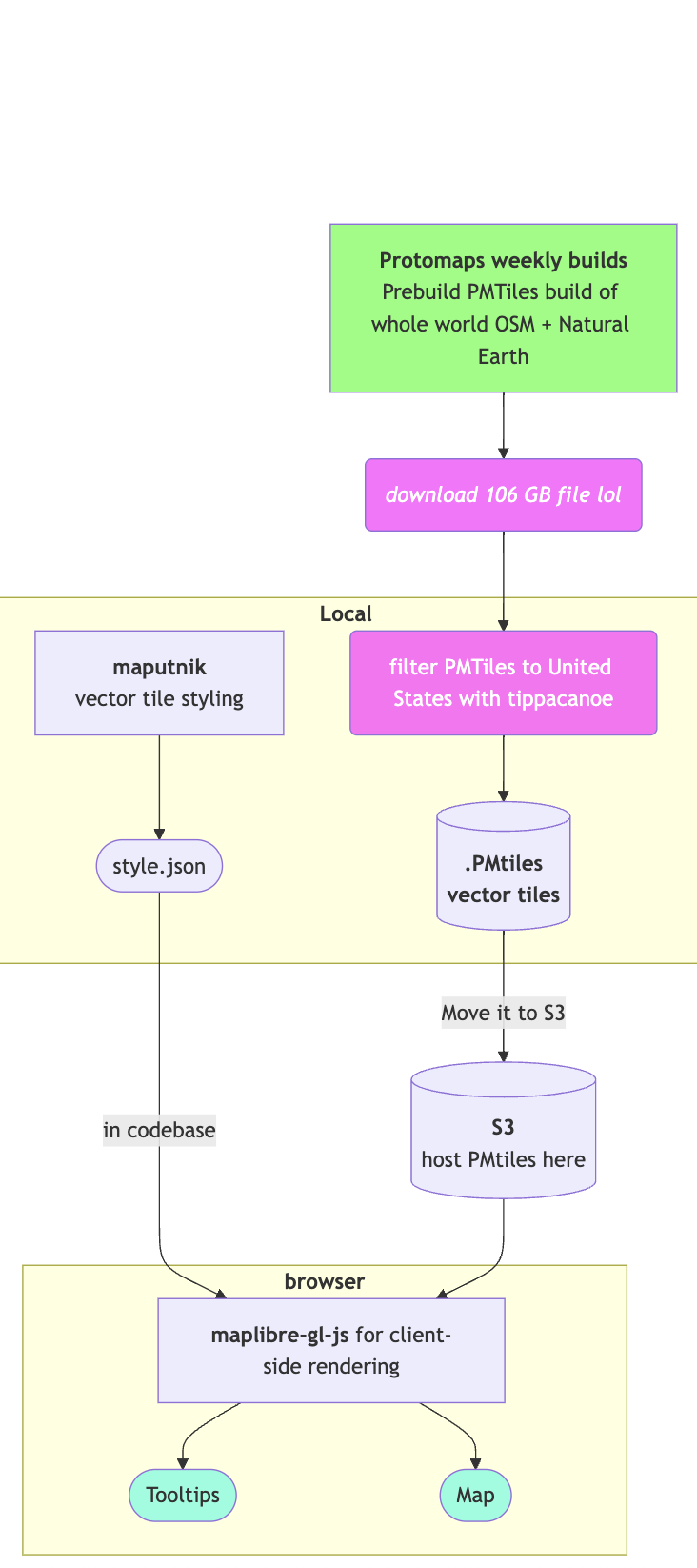

Thankfully, Amico’s blog post and talk at NICAR 2024 pointed out a pathway to avoid this step: use the Protomaps weekly PMTiles world build.

Protomaps is a fully free and open-source web mapping ecosystem spearheaded by developer Brandon Liu. It includes (as described on their website):

- PMTiles, an open archive format for pyramids of tile data, accessible via HTTP range requests.

- An ecosystem of tools and libraries for creating, serving and manipulating PMTiles.

- A cartographic “basemap” showing features in the world like roads, water bodies and labels, based on the OpenStreetMap dataset, and delivered as one big PMTiles archive.

And the trick here is that Protomaps provides a copy of the whole world, downloadable for free. (See an example basemap using this data.) This contains all the data that would be available if I rolled my own tileset with OpenMapTiles, but without needing to wade into Docker and understand what a “schema” is.

Each build is about 120 GB. Assuming you have somewhere local to store that data, you can trim it to your desired area using Tippecanoe. You can also extract a specific area of your liking instead of downloading the whole world.

This simplified our workflow to the following:

Workflow with

OpenMapTiles

Workflow with

Protomaps weekly builds

Trimming the tiles by bounding box was fairly easy, and allowed us to store less than the whole world. But trimming data based on country was not easy to figure out. That’s why some Mexican and Canadian cities are in our basemap. This isn’t ideal, but it was expedient. If we really needed to trim these things out, I think we’d have to use something like OpenTileMaps, which would have given us more fine-tuned control over what data goes into the basemap. (But if you know a better way, please let me know!)

It really IS a lot cheaper.

Self-hosting maps, beyond being daunting, used to cost a lot more than it does now. Before the PMTiles filetype existed, hosting vector tiles required either a server-side component (a “tile server”) or pre-baking every tile at every zoom level — and uploading and hosting all those individual tiles.

But with PMTiles you do not need to run a server to host and deliver vector tiles. Instead, you only need to drop the big PMTiles file somewhere accessible (S3 for instance, and ideally behind a CDN like Cloudfront). And Protomaps relies on the magic of HTTP range requests, where users only request the small portion of the PMTiles file that they need at any given time. The result: You can self-host maps at a substantial savings.

Protomaps provides a handy cost calculator to estimate a project’s costs versus other hosted options. I adapted this for my own calculator in Google Sheets .

Here are some topline things we learned:

The real cost is transfer from S3 to the browser

(Caveat: All these estimates are based on prices and polices at the time of publishing.)

- About 90% of the costs are for bandwidth from Cloudfront (Amazon’s CDN) to the internet. This is the total data transferred to users, and it costs about a dime for every gigabyte transferred. (And remember, users aren’t downloading the whole giant PMTiles file — just a tiny range of it.) OSM and hillshade tiles each averaged about 100 KB per tile. Our custom tiles for garden zones were much smaller. Transferring the data for about 100,000 tiles would cost $1.

- About 8% of the costs are based on the total number of GET requests made by users. Each tile requested is one GET request. Each PMTiles file shows about 4 tiles per zoom level per layer displayed. 100,000 GET requests would cost about 9 cents.

- A hypothetical scenario: If your project requests 100 tiles in an average session, and it gets 1,000 pageviews, that totals 100,000 tile requests. If your project gets 1 million pageviews in a month, your estimated costs for that month would be around $1,100. (For most news projects, the highest traffic — and costs — would come during that first month, and then trail off in subsequent months.)

It’s hard to say precisely how well the estimates matched up with reality, but they seemed to be in the ballpark.

To compare, that’s about ⅓ the cost that similar traffic might cost with a hosted service.

Don’t fret about the large size of the world map.

Storage on S3 is extremely cheap, about 0.1% of all costs for this project. Storing the WHOLE WORLD (~120GB) only costs about $3 per month. Functionally, this means storage volume is not a concern. Data transfer into S3 is also free, so there are almost no costs associated with getting huge files onto S3.

Most requests to get data out of S3, including PUT requests, do cost a tiny amount ($0.005 per request) — this is why the older strategy of generating static tiles can be an expensive proposition.

How to save money (and speed up loading!)

The main two axes to save money are:

- reduce the total number of tiles requested, and

- reduce the size of each tile.

Here’s how we approached this:

- Hide layers at certain zooms. For instance, we opted to avoid showing the hillshade layer until the map was zoomed in. This reduced the number of large tiles requested.

- Lazy-load tile layers. Initially the show/hide logic was based on the opacity of layers. This requested 3-4 more tiles than needed to be shown at any given time, which was costly and inefficient. Changing this logic dramatically improved the browser’s paint speed and saved us money.

- Cap maximum zoom level in explore mode. At a certain point, the user doesn’t need to zoom any further, so limit it to save on the number of tile requests.

- Limit exploration if it’s not essential. We really wanted to have folks be able to find themselves in the data and explore it. Sometimes this is not necessary. Limiting exploration can confine the upper end of possible costs.

Use ChatGPT (or similar) to help you understand inscrutable documentation

The Mapbox/Maplibre GL JS style spec is inscrutable:

map.setPaintProperty('2023_zones','fill-opacity',['interpolate',['linear'],['zoom'],0, 1, 7, 1, 8, 0.78, 22, 0.78 ]);

ChatGPT at least pretended to understand it perfectly. When asked what this code is doing, it explained it line by line, ending with:

“In summary, the fill opacity for the 2023_zones layer starts fully opaque at lower zoom levels (0-7) and becomes slightly more transparent (0.78 opacity) at zoom level 8 and remains at that opacity for higher zoom levels.”

Helpful!

But beware: It can also lie! For instance, I asked “Is there a way in Maplibre GL JS style to adjust the opacity only on the fill-outline property?” The correct answer is no, as far as I can tell. But ever the people pleaser, ChatGPT confidently told me:

The only problem is that transparentize does not exist in either style spec. It exists in Sass and maybe elsewhere, but not here. I figured this out with some quick Googling, but similar stochastic parroting can lead to some weird wrong turns. Buyer beware. (It’s worth noting that this hallucination took place on GPT-3.5. When I recently asked the same question to GPT-4o, it provided a more reliable answer.)

Important notes for styling your basemap

Finally, I want to share a few tools that are helpful in making your wildest self-hosted map dreams come true.

Styling your own basemap in the Maplibre GL JS style without a graphical user interface (GUI) is next to impossible. Luckily, you can use the Maputnik GUI to edit styles. (I found it much easier to use online, but there is a version you can run locally.)

If you’re using tiles generated from the Protomaps weekly builds the easiest starting point is the Protomaps Light style, available in Maputnik. Open the editor, click “Open”, then scroll down and click on “Protomaps Light”. Edit the map styles to your liking in Maputnik, then export the style.json to your project. I recommend committing this file to your project so that you have a version history of your style as it changes.

(Note: If you start with a style like OSM Liberty, and try to connect it to a Protomaps tileset, you will have to tweak layer names in style.json to match Protomaps’ basemap schema. For instance, your source layer name for country boundaries will need to change from “boundary” to “boundaries”. These sorts of things are devilishly difficult to identify!)

To add your preferred fonts to the style.json, you will need to create the appropriate .pbf files for each zoom level and style. The MapLibre font maker makes this a cinch. Store the generated .pbf files on S3 and reference that location in your style.json.

Similarly, you may need to make a custom sprite sheet. A sprite sheet is a single png that contains all icons and symbols that you might see on a map. A json key tells the mapping software what section of the sprite sheet to slice and use for the desired symbol.

In our case, we didn’t really have any conventional icons that were needed. But in order to avoid including a large legend on every map page, and for accessibility reasons, we wanted to include a layer that would show the hardiness zone names repeated across the map.

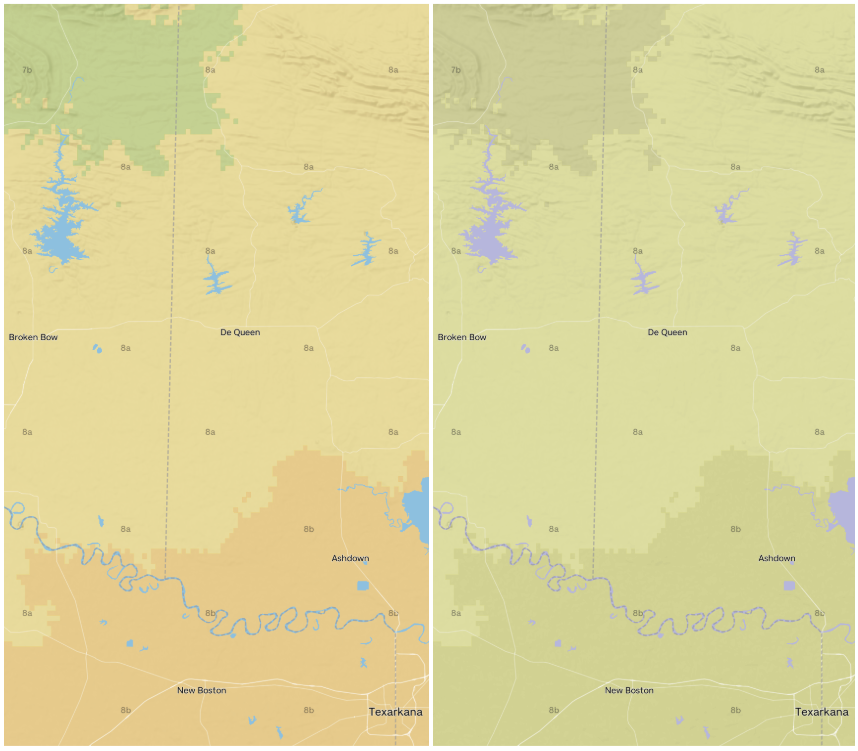

Left, the map in full color. Right, the map as it may look to someone with deuteranopia color blindness. In this view, you can see how the repeated zone labels would help readers distinguish between zones 7b and 8b.

There are a few solutions out there to create custom sprite sheets; I found that Spreet worked like a charm.

Great strides, but there are other costs to consider

The recent advances in self-hosted web maps are really exciting, but it’s important to remember a few caveats:

Hosting maps with a commercial provider like Mapbox comes with a raft of support and a more polished toolset. While the community around self-hosted solutions is robust and often available to help, there is no dedicated support if you go this direction.

Learning new tech is time-consuming and daunting. If you feel overwhelmed, look me up on the internet or in the #maps channel of the News Nerdery Slack group and ask for help! Also, I recently presented on this topic at the NACIS conference in October (as did Protomaps’ Liu).

Good luck!