In 2025 so far across 48 open tournaments, the IBJJF has given out approximately 25,000 (9,300 gold, 7,357 silver and 8,324 bronze) medals to juvenile, adult, and masters competitors, which surely you have noticed all over Facebook and Instagram. What you might not see though, is that more than a third (8,312) of those medals were given when the participant either had no matches (default gold) or lost their only match (default silver or bronze).

Now, I’m not here to de-merit the guy who posts about getting silver in a two-man division. This is just a data project illustrating where all the medals are going.

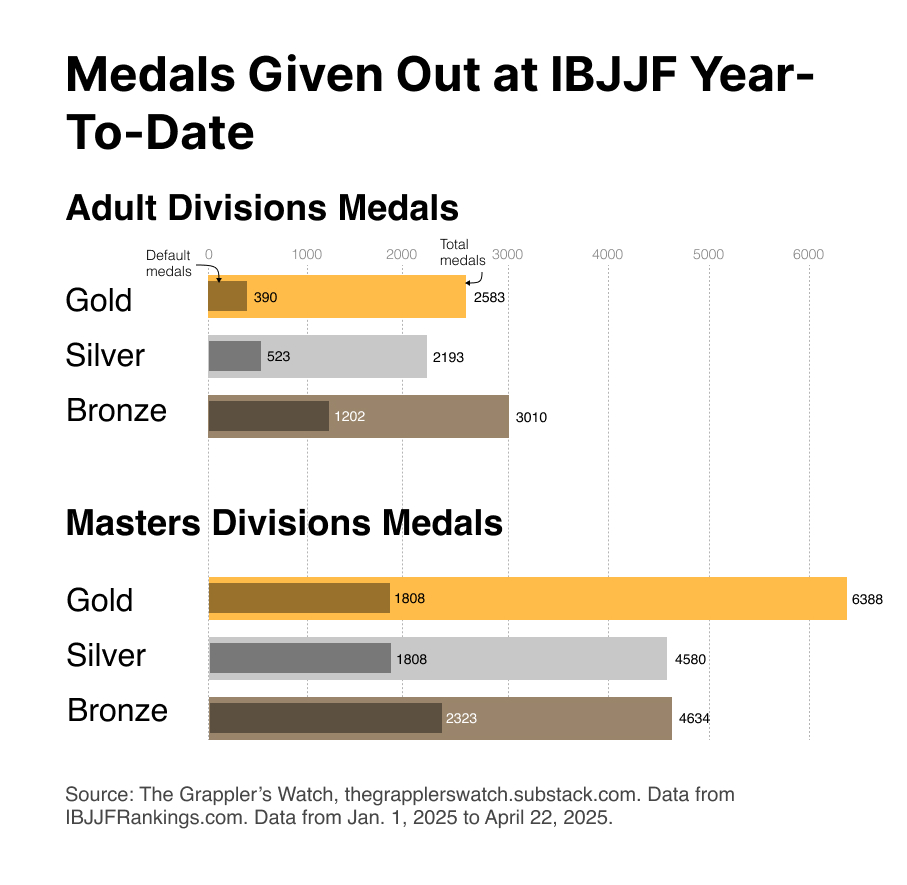

There are a lot of default medals in the masters divisions.

74 percent of all default medals were awarded in the masters categories, where divisions tend to be smaller.

More than a quarter of all masters division gold medals were single person divisions or divisions where two competitors signed up but only one showed up. 39 percent of masters silver medals were awarded for losing one match, and half of all masters bronze medals were awarded for losing one match.

By sheer numbers, black belts are picking up the most default medals.

One way of looking at the data is by raw numbers, although this might also approximate division sizes. There simply are not that many masters 4, 5 or 6 female athletes, so they naturally didn’t collect as many default medals. Generally, there is a tendency of more default golds in the black belt divisions, where there are usually also more athletes.

Female athletes are getting more default golds.

Another way to slice the data is by percentage. So, of all the gold medals earned this year so far, what percentage of them were snagged without a match taking place? Women in almost every category were more likely to stay in single athlete divisions or show up to a two person division where the other athlete no-showed.

There are just a lot of medals out there.

For a little perspective, every IBJJF tournament offers registration across 95 adult divisions and 665 masters divisions. You can do this math on your own — 9 and 10 weight divisions for female and male athletes (including open class) x 7 age divisions (adult, masters 1-7) x 5 belt color levels (white through black). Not every division has participants, but that’s a maximum of 760 divisions x 4 medals per division, or up to 3040 medals per tournament.

In reality, a major tournament like the IBJJF Europeans handed out around 2,000 medals. A regular IBJJF open tournament (Atlanta Winter, Virginia Summer, etc) might hand out on average around 500 medals.

In any given open, we’re looking at around an average of 50 default gold medals, and another 130 silver and bronze medals that were won without winning a match.

Why would anyone collect a default gold medal anyway?

There are a couple logistical reasons someone might show up for their free medal.

In the colored belts, being on the podium qualifies you for open class, where you can get more matches.

A gold medal earns your 27 points for your weight division and 40.5 points for your overall IBJJF ranking, which affects your seeding at future tournaments.

At adult black belt, you need those points to qualify for Pans and Worlds

That being said, the IBJJF offers a full refund if you’re alone in your division by check day, so you have to do the personal math if the above reasons are worth your 130-170 USD registration fee. Plus, Instagram clout!

If you want to earn gold by winning, you’ll probably have to win two matches.

When we take a look at the distribution of gold medals this year, most of them were won after one or two matches. In bigger divisions at open tournaments, some will require three wins (up to 8 people in the bracket) but rarely more than that.

A lot more people sign up for grand slam tournaments, and a big one like Pans might be the first time a competitor has to shift from winning two matches to winning three or four matches to win. Adult male colored belt divisions might have to win up to six matches for gold, and many of the masters male black belt divisions have to win up to five. One lucky guy in adult male blue feather fought a record (this year) of seven matches in his division to win gold at Europeans.

This might have implications on how you train for a major tournament. Even if an athlete can win multiple opens taking out one or two opponents at a time, they’ll need double the mental and physical grit to do it against three to five opponents on the same day at a major.

About the data

Thanks to Will Weisser and IBJJF Elo Rankings for providing the match data for this project. IBJJFRankings.com ranks competitors and provides a comprehensive database of matches in events run by the International Braziliation Jiu-Jitsu Federation. It is an independent site and are not affiliated with the IBJJF.

Support my work

These articles take me an average of 10 to 12 hours to analyze data, make charts, and write. If you would like to support me, please check out my jiujitsu sticker shop.